Clara Barton

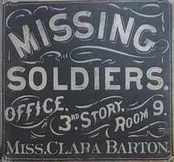

In November 1997, Richard Lyons peered into the dark clutter in the attic of 437 Seventh Street, inspecting the building in preparation for its planned demolition. His eyes settled on a sign, "Missing Soldiers Office, Clara Barton, 3rd Story, Room 9." He had stumbled upon, and saved, the home and office of the Civil War nurse and Red Cross founder, known as the Angel of the Battlefield. It was a time capsule. Room 9 was still stenciled on the door; 19th-century wallpaper hung from the walls in shreds.

It was from the spot where you now stand that Barton began her work on the Civil War battlefield in 1862, leaving for the front lines at Antietam atop a supply wagon loaded with donated food and medical supplies. She worked as a copyist in the Patent Office at Ninth and F Streets from 1861 to 1865. As a woman, she could not serve in the Union Army, so she devoted herself to feeding , nursing and comforting thousands of Union wounded in the nation's most costly war, a conflict that took more than 600,000 American lives.

After the war, at her own initiative and expense, Barton made her Seventh Street home a headquarters for the search for missing soldiers. She was eventually paid a flat fee of $15,000 by the government for her efforts. Thus she was the first woman to run a federal office. She received more than 63,000 letters of inquiry and wrote 41,855 replies, in the end identifying about 22,000 of 62,000 missing soldiers.

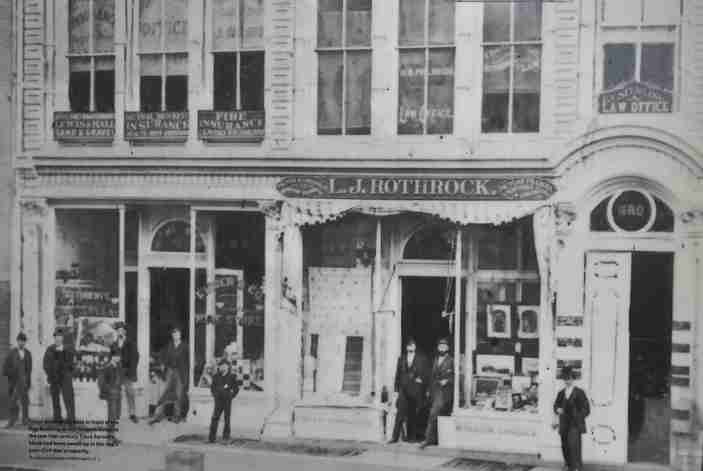

Seventh and D Streets in 1863 when Clara Barton's office was just a few steps up the street off the left side of the picture.

Proud proprietors pose in front of the May Building at 480 7th Street in the late 19th century. Clara Barton's block had been swept up in the city's post-Civil War prosperity.